Kerem Oktar

PhD Candidate,

Princeton University

📃 CV

🏠 Home, 📈 Publications,🎓 Scholar, 🐦 Twitter,

🟦 Bluesky

A Guide to the Hidden Curriculum

Here, I clarify the expectations, norms, and reality of academia.

Chapter 1: PhD Applications.

This Chapter is a guide to navigating PhD applications.

Before you begin, know that this is a hard process, and that you will really benefit from some help. If you do not have professors or friends in academia, and especially if you come from a disadvantaged background of any sort, I strongly suggest reaching out to Project SHORT. It is a free, international application support program that pairs you up with a PhD mentor. I’ve been volunteering with them for years, and it’s been a great experience!

Last Updated: 01/2024

- Section 0: Should you choose academia?

- Section 1: General application advice.

- Section 2: How to build a network.

- Section 3: How to prepare the application materials.

- Section 4: How to interview.

Section 0: Should you choose academia?

At its best, academia is wonderful (literally). We contemplate the deepest mysteries of the universe, expand the frontiers of human knowledge, and consume ungodly quantities of caffeine.

As such, many guides to grad school applications assume that you want to do academia. As time goes by, this implicit assumption becomes an expectation, and many find themselves stuck. Since you are thinking of applying now, it is extremely important that you frame this to your self as a choice, and evaluate it as such. This is your choice for how to spend the next 5-7 years of probably the most youthful, healthy, and independent years of your life.

How can you make a decision like this? The following factors are the most relevant:

How likely are you to get an academic job after doing a PhD?

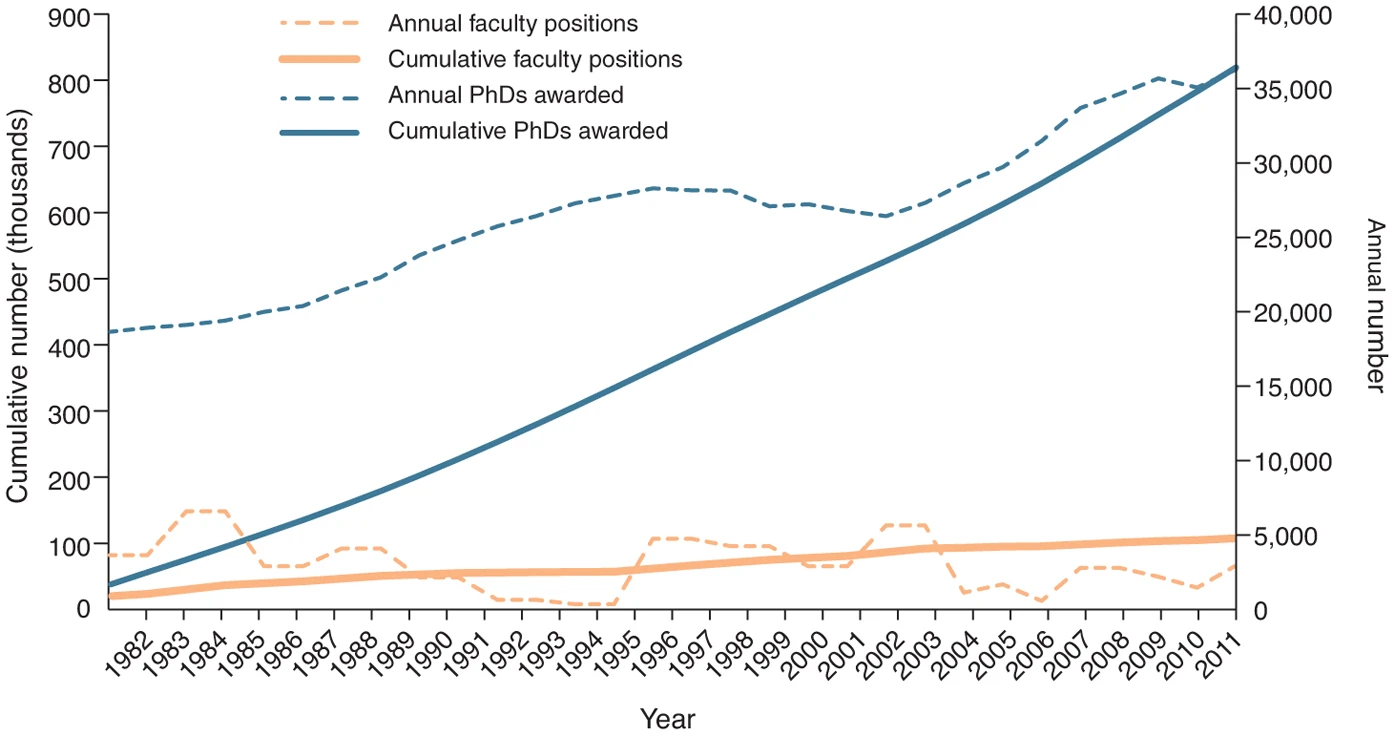

This depends on how many academic jobs there are, relative to people with PhDs. A survey of STEM fields from 2013 shows that less than 10% of PhDs could get academic jobs a decade ago; now, it’s much worse.

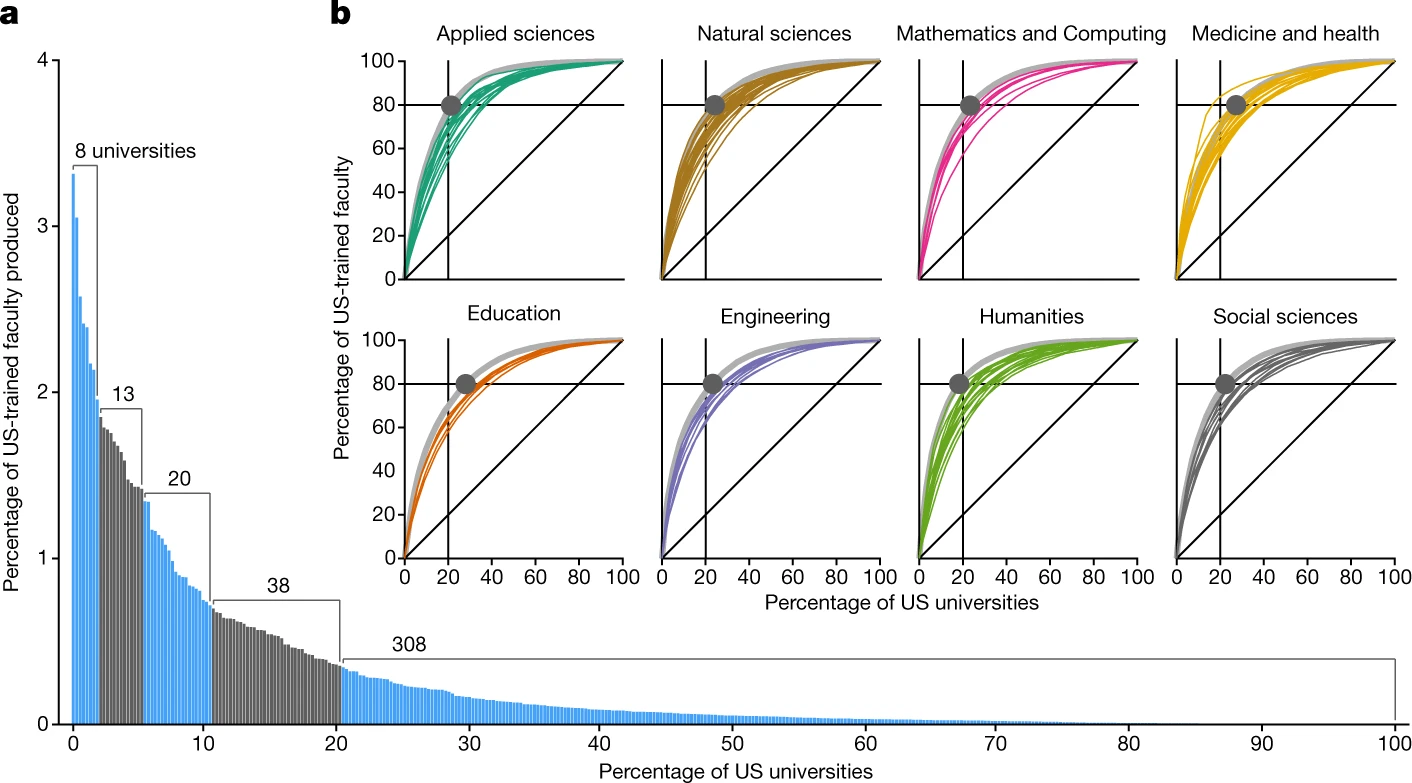

So the odds aren’t great, especially considering that the average PhD grad is quite smart, competitive, and capable. Who are the 10% that get jobs then? Mostly graduates from elite programs: 80% of those that get jobs come from the top 20% of universities, according to a 2022 paper. There is striking inequality even within the top 20 programs:

So everyone doesn’t really have a 10% chance: At best, placement can be around 30%. And when we look at jobs at the most elite institutions, 95% come from the top 25% of schools. Moreover, you are twice as likely to become faculty if you have a parent who is a PhD, and parents of faculty tend to be much wealthier than average (see this 2022 paper for on socio-economic roots of faculty).

In a nutshell, getting good academic jobs is extremely challenging - even for those who are privileged and in elite schools, but especially for those who are not. Keep 10% in mind as a baseline for your odds.

How will getting a PhD impact your career prospects outside of academia?

It depends, but overall, an analysis by the Economist claims that PhDs don’t confer advantage or employment benefits beyond master’s degrees, and that advantage is roughly a 25% increase over Bachelor’s degrees.

But this average hides tremendous variation: If you change fields and end up with a good degree in a highly employable field (e.g., AI/ML/Econ), your job prospects will likely increase a lot. Similarly, if you are an international student from a struggling economy, doing a graduate degree can help you emigrate, which will improve your prospects. And if you get into a good school you can build a strong network.

How much will I enjoy the PhD process?

This also depends, but overall, around a third to half of graduate students are depressed or anxious, a much higher rate than the U.S average of around ~10-20%. The outlook for underprivileged students (minorities, international students, LGBTQ+ groups, etc.) tends to be worse, according to a large analysis of UC Berkeley students.

Why do graduate students struggle so much? The following are all important factors:

- Graduate students lack power. If you are stuck with an advisor whose expectations are misaligned with yours, or are in a toxic environment, it can be hard to pivot or hold people accountable.

- Graduate students are not paid well. Especially for students with dependents or financial hardship, this can be a major stressor.

- Graduate students face a difficult job market. Many come in plannnig on becoming professors, and feel despair when confronted with the reality of the market.

- Academics face constant rejection. Papers, grants, talks, job applications, etc. all have much higher odds of getting rejected than accepted. And it will sting, because you will have put in a lot of effort–sometimes hundreds of hours.

So it is often rough. But obviously there are major upsides in many cases:

- Flexibility and freedom. You get to make your own schedule and routine, work on the things that interest you the most, and take on additional responsibilities as you see fit.

- Victories can be very rewarding. Your students grow and learn, your ideas develop and are cited, and these can be very satisfying.

- Respect. In general, academics are trusted and well-respected, and I think people enjoy knowing that they are doing something that is societally valued.

- Community. Academics are typically curious, quirky, and passionate. So it is relatively easy to make friends with interesting people.

In sum, academia is a challenging experience with sparse and uncertain rewards. Many struggle deeply during it, many thrive, and you should expect it to be more difficult than most alternative careers.

So should you get a PhD?

This may sound quite bleak. And it can be, for many. Of course, some academics are quite happy with their decision to pursue a PhD (I happen to be one). But it is important for you to know the facts, take some time to reflect, and make an informed decision about whether you want this for yourself.

Section 1: General Application Advice.

I will now assume that you are set on applying, and walk you through the process.

Here are three key tips:

- Understand that the goal of admissions is identifying who will do research most effectively.

- Your goal is therefore to convey that you are (or have the capacity to become) an outstanding researcher.

- Students often get this wrong. You are not trying to convince them that you are the smartest person, nor the one who most deserves this career, nor the person most interested in the field, nor the most accomplished academically. You are trying to convince them that you can develop into a good researcher.

- The best way to do so is through evidence of past research involvement. All the other considerations above can be inferred from the research you have done.

- Your goal is therefore to convey that you are (or have the capacity to become) an outstanding researcher.

- Apply widely.

- This increases your odds. Think of your applications sort of like lottery tickets (there is a lot of stochasticity in admissions processes): if you apply to 1 program, and you have a 10% chance of getting in, you probably won’t get in. If you apply to 10 programs, 1 - (0.9)^10 = 65% chance of getting in; with 20, it’s 88%! This is a terrible approximation, of course, but the point is that you are much likelier to get in if you apply widely (7 would be a reasonable lower bound).

- This holds even if you think you are guaranteed to get in somewhere. I know of cases where professors made promises that were not kept. There are no guarantees, besides the admission letter itself.

- Be optimistic.

- Assume that you have a shot everywhere. The application process is extremely chaotic–faculty have motivations and interests that are hidden from you and you are competing against a set of people that you don’t know anything about. So it is in your best interest to apply to the places that you are most excited about, and that have the most resources to support you.

- People use confidence as a signal of competence. So the more you convince yourself you can make it, the more likely you are to do so.

Now let’s get to what you can do to prepare a strong application.

I will begin the upcoming sections with quotes from The Trial, which is a book by Franz Kafka about an absurd, bureaucratic, and arcane evaluation that inspires tremendous dread in the protagonist, whose name is “K.” Sounds oddly familiar…

Section 2: How to build a network.

The only things of real value are honest personal contacts (…). That is the only way the progress of the trial can be influenced, hardly noticeable at first, it’s true, but from then on it becomes more and more visible. (pg. 139).

You should reach out to graduate students and faculty, as early as possible, but also throughout the whole process.

Why you should reach out.

Talk to faculty to:

- Get your name out there. Sometimes just being familiar with a name can allow it to stand out in a pile of applications.

- Learn whether they are taking students. Not every professor takes on graduate students each year, and it can be a waste of your money and effort to apply to work with a professor who is not taking students that year.

- Hear about what they are excited about. Sometimes a professor will want to pivot to a new research direction, and the only way to learn about that (and use it in your application) is to ask them directly what they are excited about.

Talk to grad students to:

- Learn about which labs are good and which are bad. Unfortunately, many labs have serious problems: Some are abusive, some are underfunded, some are hyper-competitive… and professors will not tell you about these things. Grad students are the only way to learn about these.

- Sometimes it is easier to learn about a lab from a grad student who isn’t in that lab—some faculty are so toxic that their students will fear retaliation and pretend they are having a great time to applicants.

- Get mentors. Graduate students are often willing and have the time to coach aspiring students through the application process.

- Get involved in research. Often, graduate students have projects that they could use help with. Talking to them is the easiest way to get involved in research, since faculty are much harder to reach.

How to make first contact.

How should you reach out? Email them. Here is a good guide to writing these emails.

How to talk to them.

First, you should know that the more you talk to strangers, the easier it gets, so don’t worry about it being stressful. It can actually become really fun!

The most important thing is to go in with specific questions or aims. The ‘why you should talk’ section above lists excellent reasons to have a conversation with someone. Just be prepared for your meeting.

Here are some more general social tips for how to talk:

- Become genuinely interested in other people.

- Smile.

- Remember that a person’s name is to that person the sweetest and most important sound in any language.

- Be a good listener. Encourage others to talk about themselves.

- Talk in terms of the other person’s interests.

- Make the other person feel important - and do it sincerely.

These are from How to Win Friends and Influence People. I haven’t read it but have heard good things from people unfamiliar with American professional social customs.

The key idea is to think of these conversations as attempts at building friendships with people who you really respect.

How to follow-up.

Once you’ve had a chat, your job isn’t over! You should circle back and thank them for the conversation, and check back in about any things you left for future conversations (e.g., to schedule another conversation about a potential project, or to discuss another topic). There are some templates here. Remember not to pester anyone with questions, though.

Section 3: How to prepare the application materials.

Needless to say, the documents would mean an almost endless amount of work. It was easy to come to the belief, not only for those of an anxious disposition, that it was impossible ever to finish it. (pg. 152).

Every admissions website tells you what documents they want: minimally, the personal statement and the CV. Here are four tricks to getting them done well:

- Learn what it takes. It is much easier to write these if you figure out what they want from you, before you start working on them.

- MIT has excellent guides on the personal statement and the CV/resume. Read these now, and carefully look at the annotated examples at the bottom of the page.

- Emphasize your research experience. One mistake I see people make often is stating that you are naturally curious, have broad interests, and love learning—-which are probably true—but your primary emphasis should be on how all of these wonderful qualities about you come together to help you do good research (see General Advice Tip #1).

- Read good examples. To some extent, learning how to write these documents is about seeing a lot of them. So search the internet for successful application materials; there’s a ton (e.g., google ‘Harvard personal statement example’). Noah Reed has an outstanding collection of recent materials on his page that you can read through.

- Get feedback on your materials. It is really hard to read through your materials for the Nth time and get new insight. Have anyone willing to read give you feedback.

- Tailor your application. In some fields (like psychology), you do not just apply to a department, but to work with a specific person. You want this person to feel like you are the perfect fit for them.

- Emphasize research alignment. The idea here isn’t so much that you should make yourself seem like someone a professor would like to work with, but to make sure you find the faculty who best align with your previous research experience. Because you will have the easiest job convincing them that you can do quality research in their field.

- Reach out. You can’t tailor a suit without knowing who you’re tailoring for! Email the professor and the people in their lab — they will know what the current research directions are (and whether you want to work with this person at all).

- This all holds even if you are applying to a department. You may just have to tailor your application to a few faculty instead of one.

- Work consistently. You should expect each document to take multiple (5-10) drafts to get right. Often you will have to start over. The only way you will have time for that is if you start working early and consistently.

- What has worked for me is having external accountability: Break your task into chunks, and tell someone that you will have the chunk ready for them by a certain time. The more the chunks, the more the deadlines, the less likely you are to just procrastinate until the final deadline.

- You can try to read some self-help book summaries.

- Be kind to yourself! This is a hard process - if you find yourself resembling this Kafka drawing:

You should stop and go for a walk. Schedule breaks and rest, much as you schedule work.

Section 4: How to interview.

This is when the defence begins. (…) he has to learn what he can about it from him and extract whatever he can that might be of use, even though what the accused has to report is often very confused. (pg. 138).

Congratulations on making it to the interview stage! If you are here, you have already cleared the vast majority of the hurdles, and should feel very proud of yourself.

Project SHORT has some excellent resources, such as a description of the general structure of the interview, prep tips, and what to expect.

The only thing I will add to this is that your interviews are primarily about you. It is a mistake to just read faculty’s papers or prepare generic questions. The most important thing to figure out is what you want to do.

- Think about a couple projects that you would be really excited to do. What would some experiments look like? What would the experiments tell us? What would be challenging about them (e.g., confounds)? Who in the lab could you collaborate with on these projects?

- The more concrete your vision, the easier it will be for you to communicate it.

Thanks for reading, and best of luck! If you would like to send me anonymous feedback, about this guide, please click here.